In the vast landscape of Bengali cinema, Satyajit Ray’s Goopi Gyne Bagha Byne trilogy holds a unique place—a series of films that, while intended for children, captivates audiences across generations. Consisting of Goopi Gyne Bagha Byne (1969), Hirak Rajar Deshe (1980), and Goopi Bagha Phire Elo (1992), this fantastical saga about two unlikely heroes—Goopi, the singer, and Bagha, the drummer—has become a cultural landmark. Yet, with the passage of time and the onslaught of contemporary cinema, many younger Bengalis may be less familiar with the magic and relevance of these timeless classics.

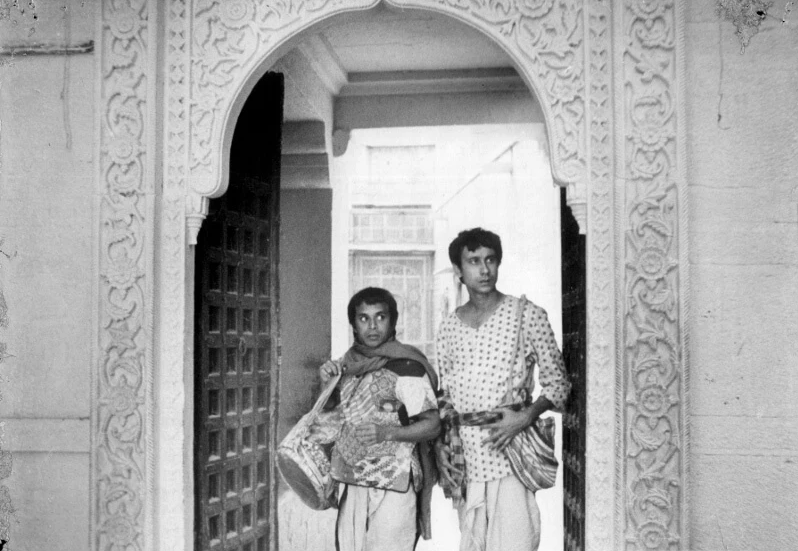

Goopi Gyne and Bagha Byne are two hopeless but well-meaning musicians whose talents leave much to be desired. Goopi’s singing makes his fellow villagers run for cover, and Bagha’s drumming isn’t much better. Both characters are outcasts in their respective villages, yet it is precisely this sense of rejection that bonds them together. When they meet in a forest and decide to play their instruments together, fate grants them an extraordinary twist of fortune. They are given three boons by the King of Ghosts, a device Ray uses to bring magic and humor into the narrative.

The boons—a wish for limitless food, the power to travel instantly, and the ability to mesmerize people with music—shape their adventures and misadventures, transforming the duo into unlikely heroes. Throughout the trilogy, Goopi and Bagha face adversaries not only in the form of external villains but also in societal structures that question their worth. The two characters symbolize the triumph of simplicity and innocence over greed and malice, themes that resonate deeply with today’s audiences.

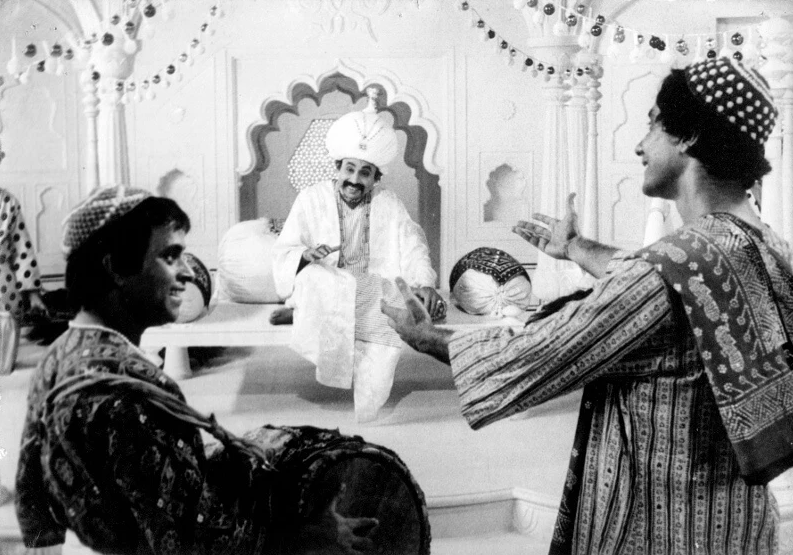

Ray’s cinematographic genius is apparent in all three films, though each entry in the trilogy displays a distinct visual tone. For Goopi Gyne Bagha Byne, shot in black and white, Ray crafted a world filled with simple yet evocative imagery. Subrata Mitra, Ray’s longtime collaborator, brought Ray’s vision to life with an enchanting balance of magic and realism. One of the most iconic scenes in Goopi Gyne Bagha Byne is the Bhooter Nach (Ghost Dance), a surreal and mesmerizing sequence that captures the essence of Ray’s playful imagination. The scene occurs when Goopi and Bagha encounter the King of Ghosts, who grants them their magical boons.

The choreography of the dancing ghosts, combined with Ray’s haunting music and inventive use of lighting, creates a blend of whimsy and eeriness. The ghosts move in a hypnotic rhythm, their ethereal forms enhanced by the striking contrasts of black and white cinematography. This scene is not just a visual delight but also a key turning point in the narrative, establishing the magical, otherworldly tone of the film.

As Ray transitioned into color in Hirak Rajar Deshe, the cinematography evolved to reflect the themes of the film. The kingdom of the tyrant Hirak Raja bursts with exaggerated colors, accentuating the grotesque opulence of a land where intelligence is subdued. The sharp contrast between the vibrancy of the kingdom and the dullness of the oppressed people is a visual cue for the audience, subtly hinting at the film’s allegory of political control and intellectual suppression. Soumendu Roy’s cinematography captures these nuances with precision, allowing Ray’s socio-political commentary to unfold visually.

The third film, Goopi Bagha Phire Elo, adopts a slightly more understated visual palette, aligning with the aged and more seasoned characters of Goopi and Bagha. Although, this film was directed by Ray’s son Sandip Ray. Yet, even here, Ray’s meticulous attention to framing and lighting persists.

Ray’s sets are as integral to the storytelling as the characters themselves. The forest where Goopi and Bagha first meet is otherworldly but grounded in the recognizable Bengal landscape. It’s a place that feels familiar and mystical at the same time.

Hirak Rajar Deshe showcases some of Ray’s most memorable set pieces. The mechanical devices used by Hirak Raja to brainwash his subjects, such as the “Magaj Dholai” machine, are not just symbols of oppression but also a reflection of Ray’s commentary on the rising mechanization of thought and society. The sets, while fantastical, are rooted in deeper truths about societal structures. The larger-than-life palace of Hirak Raja serves as a visual metaphor for the excesses of autocratic power, towering over the modest dwellings of the oppressed villagers.

The third film in the trilogy sees Goopi and Bagha in a variety of locations, from royal palaces to dense jungles, each setting reflecting the inner turmoil and growth of the characters. These set pieces, though fantastical, are deeply intertwined with the films’ thematic concerns.

Satyajit Ray, who composed the music for all three films, infused the soundtracks with a blend of folk and classical elements that continue to resonate. The first film’s songs, such as the beloved “Bhuter Raja Dilo Bor” (The King of Ghosts Gave Us Boons), are instantly recognizable even to those who haven’t seen the film. The songs are not just catchy but serve as a narrative device that pushes the story forward.

In Hirak Rajar Deshe, Ray’s music becomes more pointed, with songs like “Dori Dhore Maro Taan” (Pull on the Rope) acting as calls to action against tyranny. The use of rhyme and rhythm mirrors the structure of revolutionary Bengali folk songs, grounding the film in a cultural and political context that was deeply relevant during the time of its release.

Ray’s ability to blend satire with melodic beauty is evident throughout the trilogy, as music becomes both a tool for entertainment and a medium for social critique. For today’s audiences, the songs are not only enjoyable but serve as historical snapshots of Ray’s genius, capturing the mood of Bengal in the latter half of the 20th century.

Though their roles remain comical, Goopi and Bagha’s evolution across the trilogy is both subtle and profound. In the first film, they are wide-eyed, bumbling, and naive, happy to be caught up in events beyond their understanding. By the time of Hirak Rajar Deshe, they have matured, becoming more socially aware, using their talents and boons to fight injustice. Their heroism remains unconventional, but it is undeniable.

In the final film, Goopi Bagha Phire Elo, they are older and wiser, grappling with the consequences of their own decisions. Their progression from bumbling musicians to seasoned adventurers parallels the trajectory of Ray’s political and social commentary. What begins as a lighthearted fairy tale morphs into a deeper exploration of human nature, justice, and the importance of empathy.

For today’s Bengali audiences, Ray’s Goopi Gyne Bagha Byne trilogy is more than just a nostalgic throwback. It’s a reminder of the timeless nature of art that blends entertainment with deep, resonant truths about society. The films, while set in fantastical worlds, are anchored in Ray’s acute understanding of human nature, politics, and morality.

In an era where escapism often means detaching from social responsibility, Ray’s trilogy offers the perfect balance: it invites viewers into a magical realm while urging them to reflect on the real world. Whether for the joy of its music, the cleverness of its political allegories, or the simplicity of its characters, the Goopi Gyne Bagha Byne trilogy remains an essential watch, especially for younger Bengalis who wish to rediscover the profound beauty of their cinematic heritage.

- Link to first film – https://archive.org/details/ggbb_20220204

- Link to second film – https://www.primevideo.com/detail/0PHXJLNH2DL1QWEPDTH65XSCHC/ref=atv_dp_share_cu_r

- Link to third film – https://www.primevideo.com/detail/0RI9Q2Q1I2Y6IM19PK9I4XINYA/ref=atv_dp_share_cu_r

Leave a comment