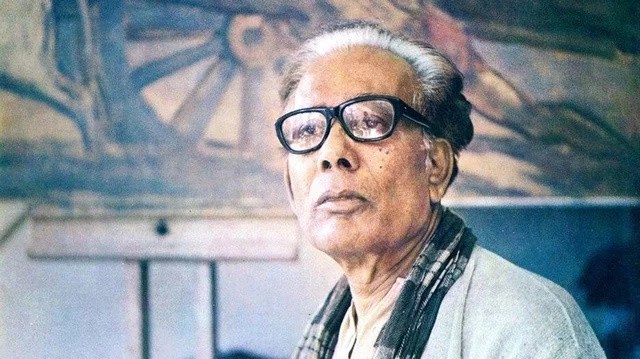

Zainul Abedin’s journey as an artist begins with the fields and rivers of Bengal, where life moved at a measured, rhythmic pace. Born in Kishoreganj in 1914, his early years were spent absorbing the sights, sounds, and textures of rural Bengal, where nature itself seemed to paint vivid pictures. The land was a quiet but powerful presence, and Zainul’s eyes were always drawn to its simple, unwavering beauty. As he grew, this connection to his surroundings would become the lifeblood of his art, a current running through all his works.

When he moved to Calcutta in 1933 to study at the Government School of Art, Zainul found himself learning the formal techniques of Western art. He mastered these, but his soul stayed rooted in the earth and water of his homeland. His mind, while expanding with new ideas, remained tied to the soil, and he brought to his work a depth of feeling that spoke to the lives of ordinary people. His lines were never just lines—they carried with them the weight of human stories, the struggle of life in a landscape both nurturing and unforgiving.

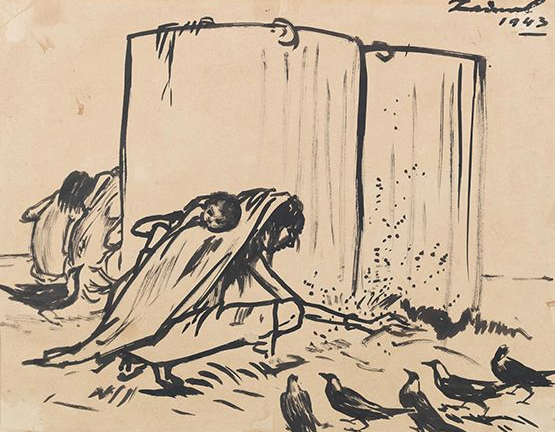

In 1943, when Bengal was struck by one of the worst famines in its history, Zainul’s art took on a new urgency. The famine had left millions of people starving, their bodies reduced to fragile shells, and Zainul could not turn away from this reality. His Famine Series is a reflection of his deep empathy for the suffering he witnessed. He used ink on paper to depict skeletal figures, capturing the desperation and helplessness of a people caught in the jaws of hunger. His strokes were quick, spare, and unflinching, creating images that haunt long after they are seen.

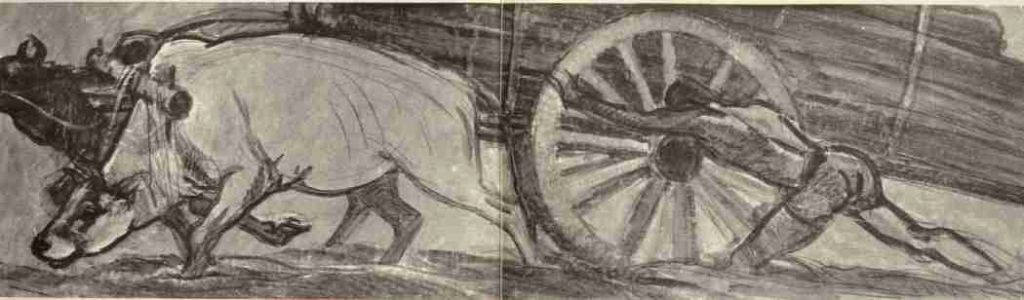

One of the most striking pieces from this series shows a mother holding her lifeless child, her gaunt face and hollowed eyes frozen in silent grief. The simplicity of the composition makes the pain more profound—Zainul stripped away all distractions, leaving only the barest essence of human despair. Another piece shows a starved bull, its ribs jutting out like blades, a once-powerful creature now reduced to a fragile skeleton. These drawings are raw and powerful, a reflection of Zainul’s ability to convey immense emotion with minimal means.

As the years passed, Zainul became more than just a recorder of his time; he became a shaper of it. After the partition of India in 1947, he moved to Dhaka, where his vision and leadership were instrumental in the creation of the Dhaka Art College in 1948. Through his teaching, Zainul nurtured a generation of young artists, urging them to look at their surroundings and to root their work in the life and culture of Bengal. He believed that art should come from the soul of a people, and his work reflected this belief—always, there was a deep connection to the land and the lives it sustained.

One of his later works, Manpura, painted in 1970 after the Bhola Cyclone devastated East Pakistan, speaks of nature’s fierce and unrelenting power. The painting is a whirl of chaotic strokes, capturing the raw energy of the storm that had claimed hundreds of thousands of lives. Yet amid this destruction, there is also resilience—a quiet determination in the faces of the people. Zainul had an uncanny ability to balance destruction with hope, portraying a spirit that could not be easily broken.

This resilience is also at the heart of Nabanna, his tribute to the farmers who work the fields and reap the harvest, year after year. In this piece, Zainul turned away from tragedy to celebrate life’s renewal. The farmers, depicted in warm, earthy tones, are caught in moments of toil and triumph, their faces weathered but proud. The land, in this painting, is not just a backdrop—it is a partner in the eternal cycle of planting and reaping, of life and death. The warmth of the work radiates a deep connection to the earth, a quiet reverence for the forces that sustain life.

Zainul’s Rebel Cow from 1971 is another landmark in his oeuvre. Here, the cow—an everyday figure in the rural landscape—becomes a symbol of defiance. Its head lowered, horns thrust forward, the animal charges with a raw, unrestrained energy that feels unstoppable. The image pulses with life, with a sense of rebellion and strength that mirrors the mood of a nation on the brink of freedom. Zainul had an innate sense of how to take something familiar and transform it into something greater—an idea, a movement, a force.

Throughout his life, Zainul remained deeply connected to the land and people of Bengal. His art never strayed far from the rhythms of rural life, and even as his fame grew, he continued to find inspiration in the everyday struggles and triumphs of ordinary people. When he passed away in 1976, he left behind not only a body of work but also a legacy of hope.

His contribution to modern art, particularly in South Asia, is immeasurable. Zainul’s paintings are not confined to canvas—they live and breathe in the fields, rivers, and streets of Bengal, in the faces of those who work the land and fight for survival. His lines, so full of grace and power, remind us that art is not an escape from reality but a mirror to it. Through his work, we see the beauty in the everyday, the strength in hardship, and the eternal connection between land, people, and spirit. In the end, Zainul’s art was never about aesthetics alone. It was about life—its rawness, its resilience, and its capacity for renewal.

Leave a comment