Mrinal Sen’s Kharij is a film that defies easy categorization. I remember the first time I watched it; it wasn’t like encountering a film as much as it was like walking into a deeply uncomfortable yet revelatory moment of life. I felt it impose a set of moral questions onto my conscience. What Sen does with Kharij is remarkable because the film does not posture or preach, and yet, by the time the credits roll, you feel like you’ve been implicated in a system that is, at once, both familiar and alien. It’s the kind of cinema that strips you of your indifference.

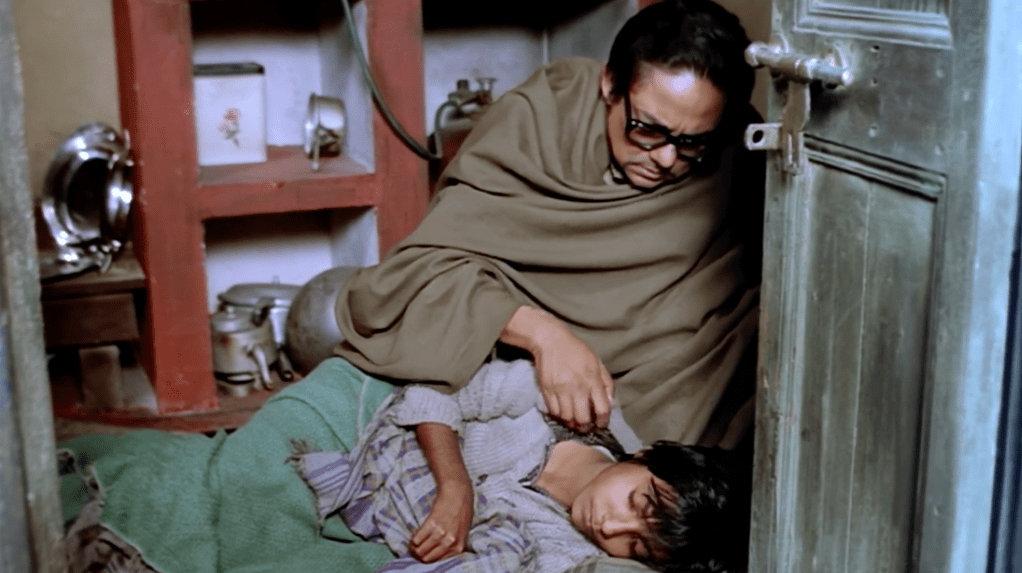

At the heart of Kharij is a devastatingly simple narrative. A middle-class couple in Calcutta, Sudhindra and Anjana, hire a young boy, named Kapil, to work as their domestic help. Kapil is merely a child, and this fact remains discomfitingly evident throughout the film, even as the couple nonchalantly accepts his presence in their household as a part of their everyday life. But when Kapil is found dead—due to asphyxiation from the fumes of a coal oven—what unfolds is less of a murder mystery and more of a searing exploration into the layers of guilt, complicity, and moral abdication that we tend to so easily live with.

What struck me almost immediately is the way Sen refuses to offer easy emotional outlets. There is no grand melodrama here. The film, like life itself, moves in subdued tones. The couple’s reaction to the boy’s death isn’t an eruption of grief but rather a quiet realization that something terrible has occurred under their roof. Sen’s genius is precisely in this restraint—by withholding emotional histrionics, he forces the audience to reflect on the subtle horrors of everyday apathy. It is, in many ways, a story that indicts not just the characters on screen but the viewer as well. And this, I believe, is where Kharij transcends the limits of narrative cinema and becomes something akin to a moral inquiry.

What makes Kharij so arresting is how deeply rooted it is in the everyday. Sen meticulously constructs a world that feels lived in, mundane, and utterly real. The middle-class milieu of Calcutta, with its cramped apartments, domestic squabbles, and unquestioned hierarchies, is rendered with such care that it becomes almost suffocating in its normalcy. The apartment in which the couple lives is small, ordinary, and yet it feels loaded with the weight of unspoken tensions.

Cinematically, Sen’s use of space is extraordinary—rooms that should offer safety become claustrophobic, oppressive even, after Kapil’s death. The visual framing of the characters, often shot in corners or partially obscured by objects, mirrors the way in which they themselves are trapped by their own complicity. It’s as if they cannot fully see each other, or themselves, in the aftermath of the tragedy. This sense of entrapment, both physical and moral, is a recurring motif in the film, and it is through this lens that the story becomes not just a tragedy of a child’s death, but a larger meditation on human indifference.

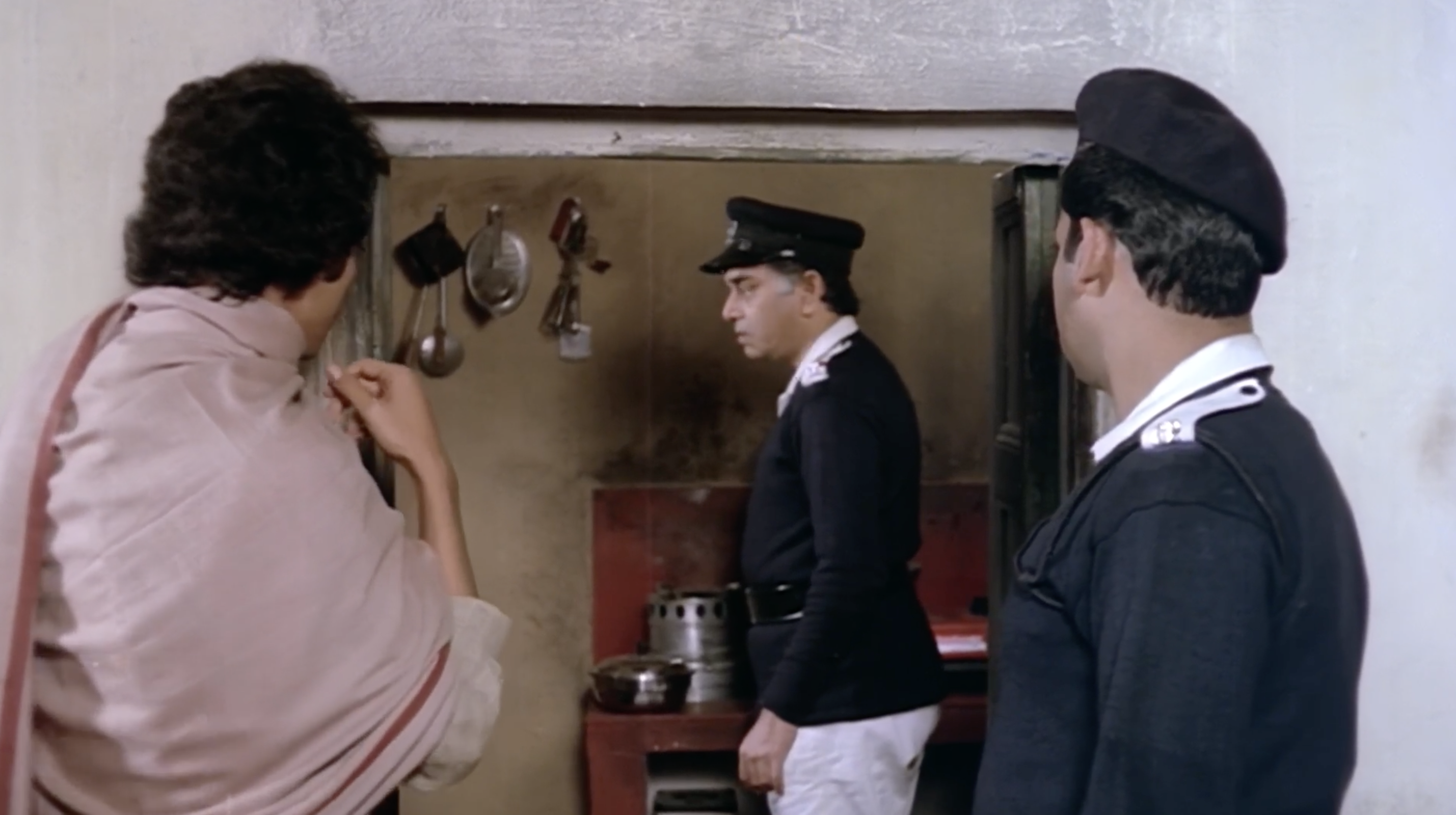

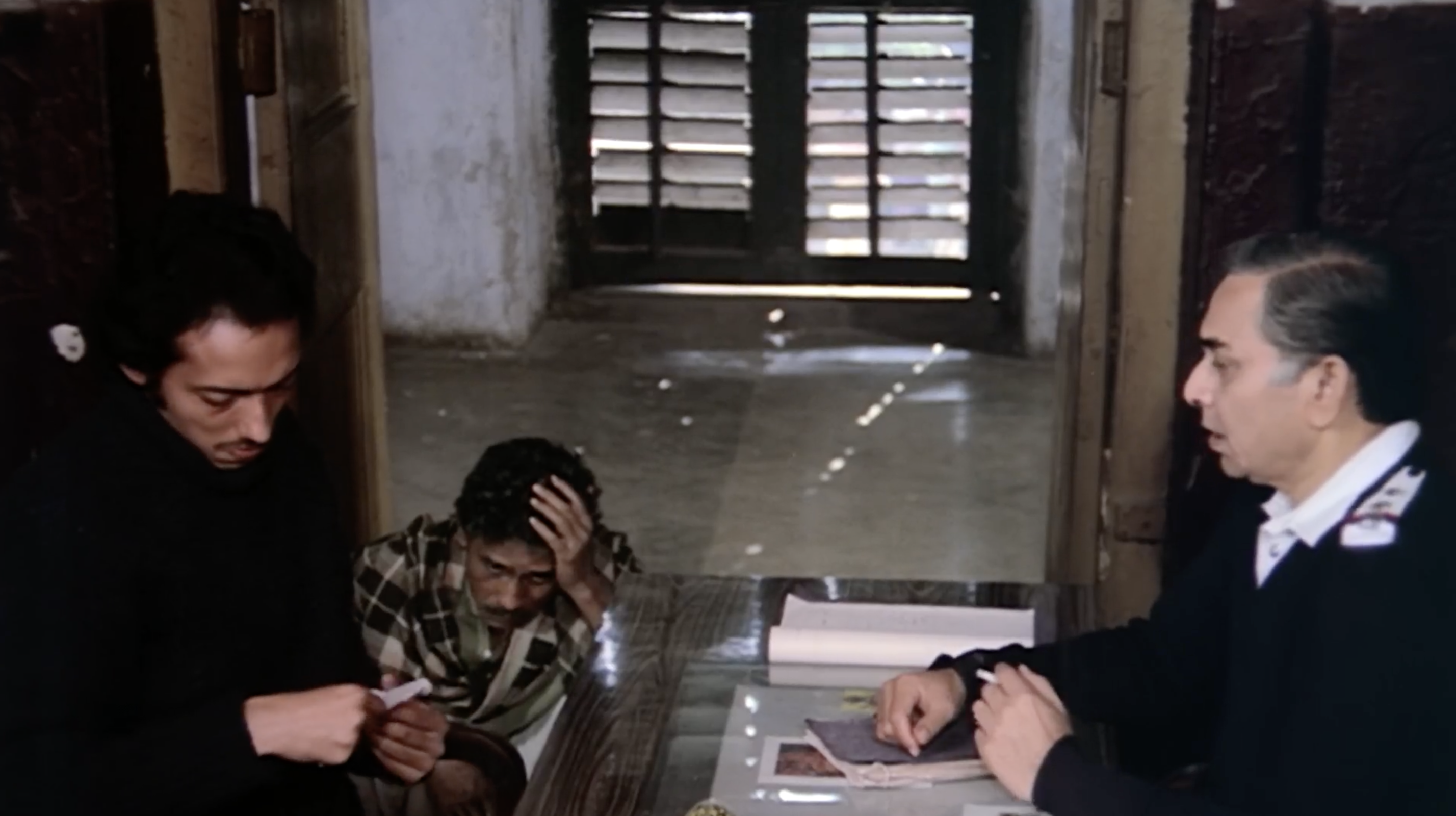

One of the most striking elements of Kharij is how it eschews traditional notions of justice and redemption. In many films dealing with the aftermath of a tragedy, there is often a sense that the characters will either seek justice or be transformed in some way by the event. Sen gives us none of that. Instead, he presents the aftermath of Kapil’s death as a slow, almost bureaucratic unraveling. The police arrive, investigations are made, and yet there is no catharsis. The couple is not painted as outright villains; they are, in many ways, as much victims of the system as Kapil was. But this, of course, is the most damning aspect of the film. The system itself—both social and moral—has such deeply ingrained inequalities that even the so-called victims become complicit in perpetuating it.

What fascinated me the most about Sen’s direction was his ability to use silence as a narrative device. There are long stretches in the film where the absence of dialogue speaks louder than any line could. After Kapil’s death, the conversations between the couple become more stilted, more fragmented, as if the enormity of what has happened has rendered language inadequate. This use of silence creates a palpable tension, forcing the viewer to fill in the emotional blanks. It’s a subtle, yet deeply effective, way of conveying the unspoken guilt that hangs over the couple like a dark cloud. Every word they do speak feels strained, as if spoken through a barrier of denial and discomfort.

The camera in the film is often used as an indifferent observer. Sen frequently adopts wide shots that place the characters in the middle of their surroundings, almost as if they are being swallowed by the world around them. This serves to underscore the fact that, in the grander scheme of things, Kapil’s death—and the moral implications of it—are but a small ripple in the larger social fabric. The world goes on, indifferent to the tragedy, and this indifference is mirrored in the way the camera observes from a distance, never fully intruding into the characters’ inner worlds. It’s a stark, almost clinical way of framing the story, and yet it’s precisely this distance that makes the film so devastating. We, as viewers, are forced into the role of passive observers, complicit in our own way by our detachment.

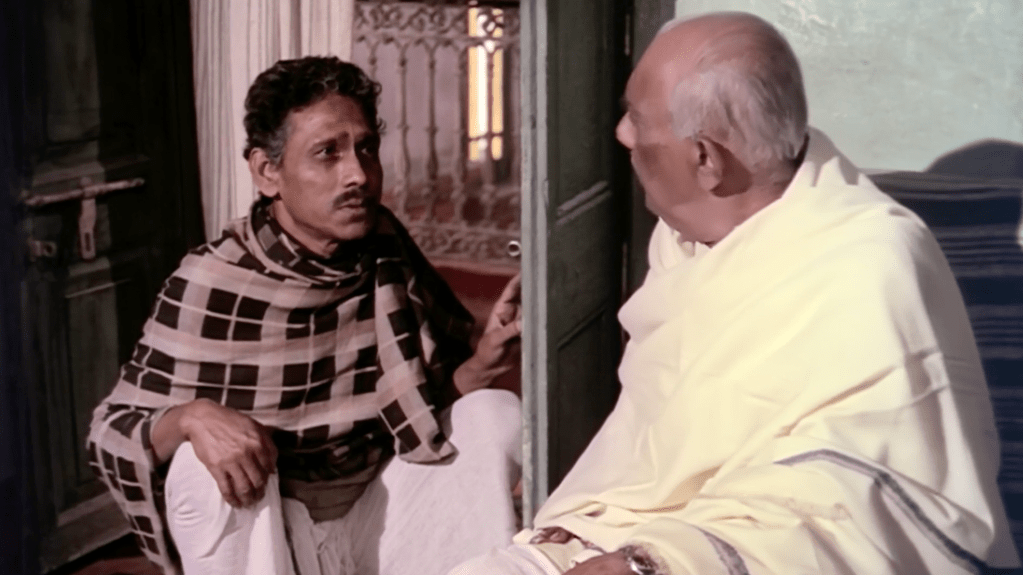

And yet, even within this detachment, there are moments of piercing intimacy. One scene that stays with me is when the couple, after Kapil’s death, must confront his father. The scene is excruciating in its quiet devastation. The father is not angry; he does not lash out. Instead, his grief is subdued, almost resigned, and this quiet acceptance of the tragedy is far more painful than any outward display of emotion could have been. Sen’s decision to underplay these emotional beats is a masterstroke—it is in the things left unsaid, the emotions left unexpressed, that the true horror of the situation emerges.

Another interesting thing Kharij is how it lingers long after the film ends. There is no neat resolution, no sense of closure. Kapil’s death, like so many tragedies in real life, is left unresolved in a moral sense. The couple will continue living their lives, perhaps a little more burdened by guilt, but largely unchanged by the event. The film, in this sense, becomes a haunting reminder of the ways in which we, as a society, are able to absorb unspeakable tragedies and continue on as if nothing has happened. This, I believe, is the true genius of Mrinal Sen’s cinema—his ability to force us to confront the uncomfortable truths about our own moral failures, without offering any easy answers or absolution.

Leave a comment