Kalighat paintings, born amidst the bustling streets and chaotic rhythm of 19th-century Calcutta, offer a masterful and sardonic glimpse into the hypocrisy of society. At first glance, these works may appear deceptively simple — watercolor strokes on paper, vibrant colors embracing figures that seem whimsical, almost playful.

Yet beneath their surface lies an unrelenting critique, a sharp, knowing gaze that strips bare the veils of morality, pretension, and societal decay. The artists of Kalighat, who toiled by the ghats near the famous Kali temple, were far more than mere image-makers. They were chroniclers, witnesses, and commentators, their brushes steeped in irony as they exposed the contradictions of their age.

To understand Kalighat paintings is to immerse oneself in the very pulse of 19th-century Bengal. Calcutta — a city where colonial modernity collided with traditional structures — was a place of both promise and dissonance. Rapid urbanization, the ascent of the middle class, and the influx of European ideas created a charged atmosphere.

Amid this maelstrom, the Kalighat artists emerged — many of them rural migrants drawn to the city’s economic opportunities. Their audience included pilgrims and curious visitors who gathered near the ghats, but over time, the scope of their influence widened as their satirical works resonated beyond mere souvenirs.

It is perhaps the irony of Kalighat art itself that what began as a commercial craft — paintings sold to satiate tourists — evolved into a subversive platform for social commentary. The genius of Kalighat art lies in its ability to distill complex social hypocrisies into stark, single-scene illustrations.

Unlike the intricately detailed religious miniatures of earlier Indian art, Kalighat paintings favored bold outlines, minimal ornamentation, and flattened perspectives that eschewed unnecessary embellishments. Their power came from their economy: a single glance told a story. And what tales they chose to tell! Hypocrisy — moral, religious, and familial — stood as their favorite subject.

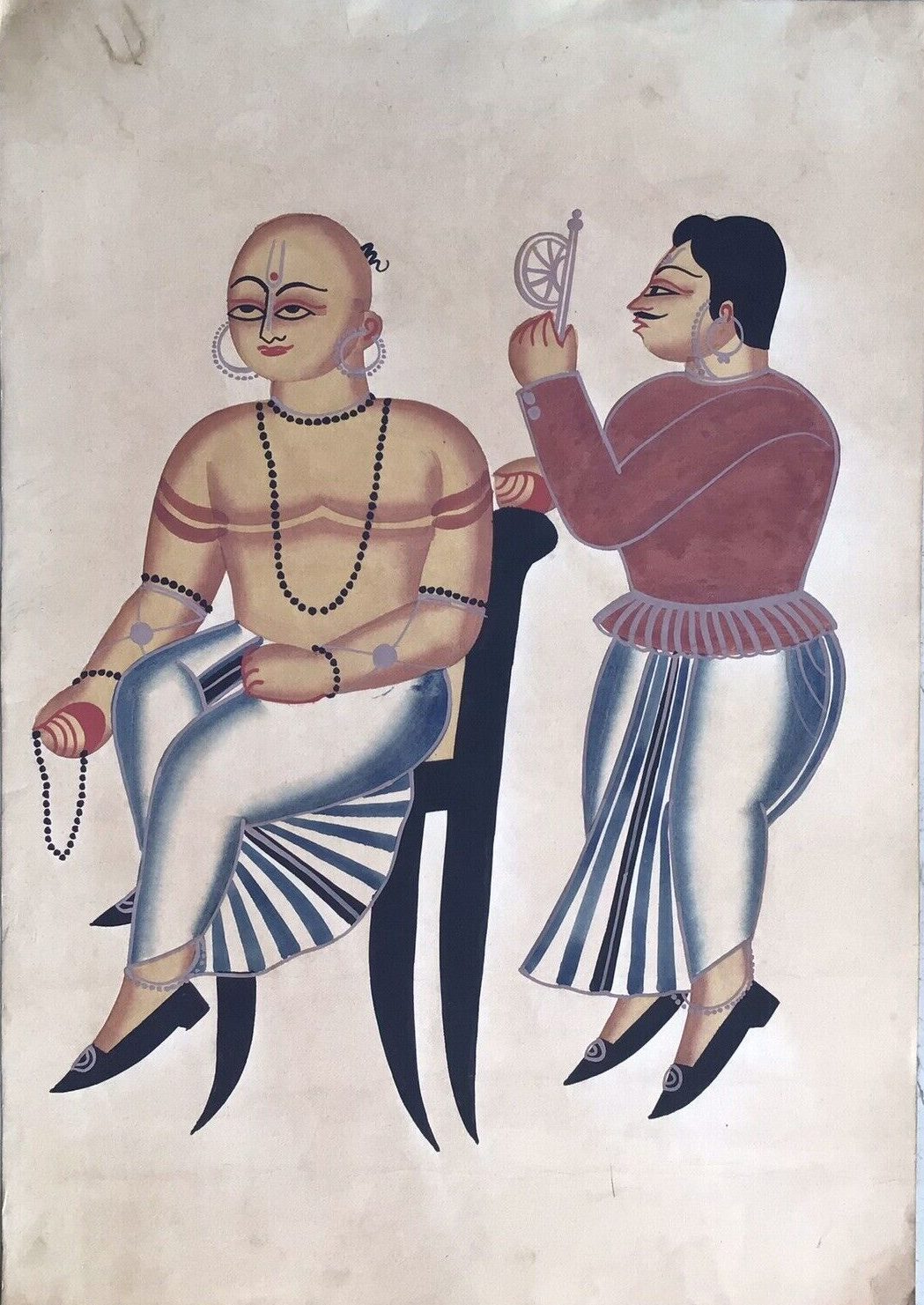

In a society where virtue was loudly proclaimed and rarely practiced, the Kalighat artists acted as satirists wielding brushes instead of pens. Take, for instance, their portrayal of the so-called holy men — the sadhus and ascetics who roamed the streets of Calcutta with a facade of piety.

In these paintings, the sadhus are often shown indulging in pleasures forbidden to the common man. These images were not subtle, but neither were the hypocrisies they targeted. They held up a mirror to society, and in that reflection, the self-righteous saw their own masks slip. Equally biting were the depictions of domestic life.

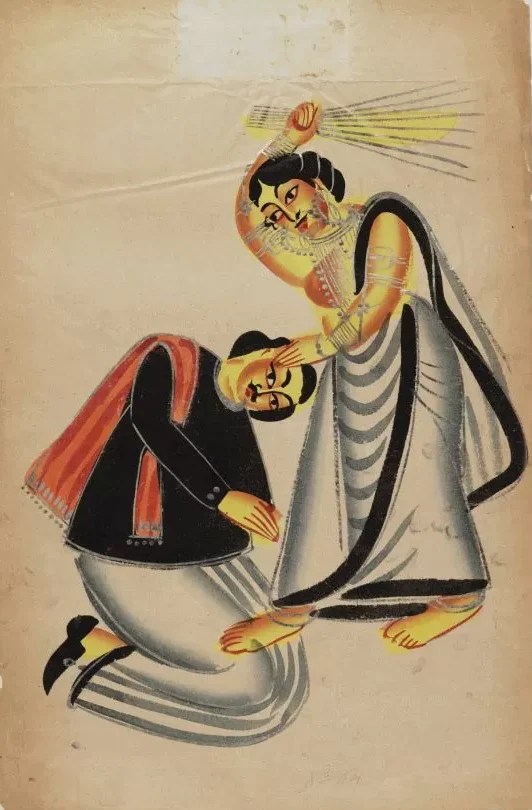

The Kalighat painters often took aim at the institution of marriage, exposing its darker undercurrents with sardonic wit. The ‘Babu’ — a quintessential figure of the urban Bengali elite — was a frequent subject of mockery. Decked in European attire, with a hat perched precariously on his head and a walking stick in hand, the Babu cuts a ridiculous figure. In one famous painting, a Babu is shown flirting shamelessly with a woman while his neglected wife stands forlornly to the side, holding a child. The satire here is cutting but layered.

The Babu, enamored with Western modernity, is as much a victim of his own affectations as he is a perpetrator of familial neglect. The woman at his side, painted with exaggerated allure, represents both temptation and the social corruption that modernity is said to have brought. This painting, like many others, strikes a delicate balance between humor and tragedy, making its critique both entertaining and unsettling.

What is remarkable about Kalighat paintings is their egalitarianism. Their themes, while deeply rooted in the urban Bengali experience, resonate across time and geography. The hypocrisy of those in positions of power — be it religious, familial, or social — is not unique to 19th-century Calcutta. Even today, one can find echoes of the Babu’s absurdity in modern-day elites — men and women obsessed with appearances, addicted to status, and yet hollow in substance.

Likewise, the spiritual pretender of Kalighat finds his contemporary counterpart in today’s public figures who pontificate on morality while cloaking their private excesses. The timelessness of these themes ensures that Kalighat art remains not just a historical curiosity but a living, breathing critique of society’s frailties.

One cannot discuss the satirical sharpness of Kalighat paintings without acknowledging their formal brilliance. The artists — often anonymous, their names lost to history — relied on instinctive mastery of form and line. The exaggerated expressions, the flowing curves, and the sparse use of space gave these works an immediacy that defied convention. Their approach to storytelling was cinematic — single frames brimming with drama and movement, moments frozen in time yet vibrating with life. The choice of medium — watercolors on cheap mill-made paper — was itself a subversion of elitism. Art need not be locked away in palatial halls or painted on canvases priced beyond reach.

The Kalighat painters democratized art, creating works that could be purchased by the common man and carried home like a secret — a sly, knowing commentary hidden in plain sight. Yet for all their brilliance, the Kalighat painters’ voices gradually faded with the passage of time. The very forces that had spurred their emergence — urbanization, colonial influence, and the growing appetite for inexpensive art — eventually consumed them.

By the early 20th century, mass production and the mechanization of art rendered the hand-painted Kalighat works unprofitable. What remained were fragments, scattered across museums and private collections, their significance often reduced to curiosities of folk art. But to view Kalighat paintings merely as artifacts is to miss their essence. They are not relics of a bygone era; they are messages frozen in pigment, waiting to be heard again.

In revisiting Kalighat art today, one encounters a profound and unsettling truth. These paintings, with their humor, irony, and irreverence, remind us of art’s role as a disruptor. They strip away the layers of social pretense, exposing the moral contradictions that societies so ardently defend. The Kalighat painters may not have called themselves activists, but their works carry the same spirit — a refusal to remain silent in the face of hypocrisy.

They challenge us to see beyond appearances, to question the roles we play and the masks we wear. In their simplicity lies their power; in their satire, a truth that still stings. Perhaps, then, the Kalighat artists were not just painters but philosophers in disguise — thinkers who, with a few deft strokes of the brush, captured the absurdity of human behavior. Their works compel us to confront ourselves, to laugh, and then to ask why we are laughing. In that laughter lies recognition, and in recognition, the possibility of change.

Leave a comment