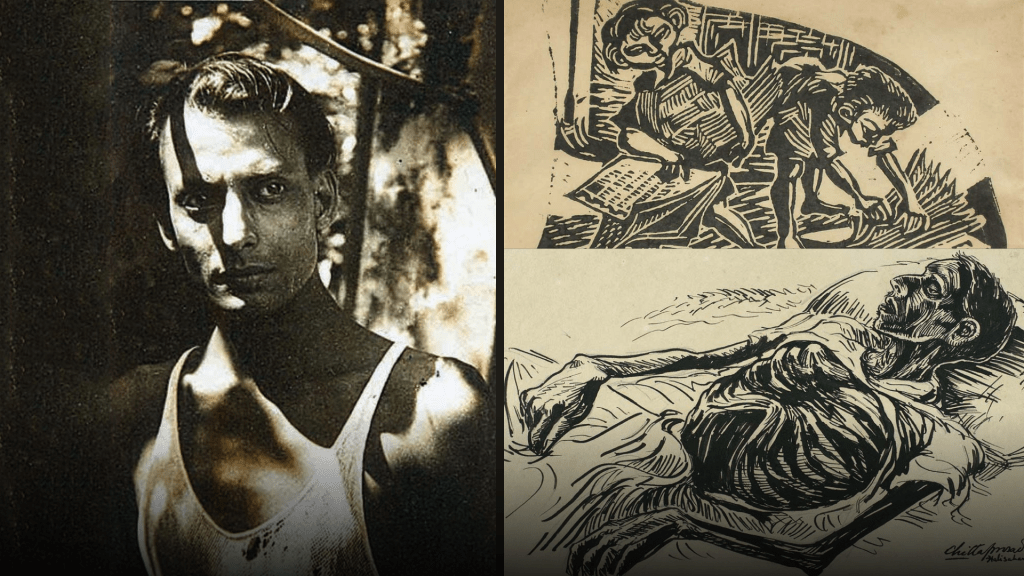

In the labyrinthine alleys of Midnapore, where the air hung heavy with despair, Chittaprosad Bhattacharya wandered, his keen eyes absorbing the silent cries of a populace ravaged by the Bengal Famine of 1943. A self-taught artist and fervent member of the Communist Party of India, Chittaprosad wielded his pen and brush as instruments of revolution, etching the visages of the starving and destitute onto paper with a rawness that defied the sanitized narratives of the colonial regime.

The Bengal Famine was the crucible that forged Chittaprosad’s legacy. This man-made catastrophe claimed the lives of an estimated three million people, ravaging rural Bengal under the shadow of a world war. It was not just a story of failed monsoons or crop failures, as the British colonial administration sought to frame it, but a direct result of political apathy, hoarding, and misguided wartime policies.

As famine swept through the countryside, Chittaprosad traveled to the affected regions, not as a detached observer but as a committed chronicler. Armed with little more than his sketchbook, he documented the suffering with a searing honesty that both horrified and mobilized.

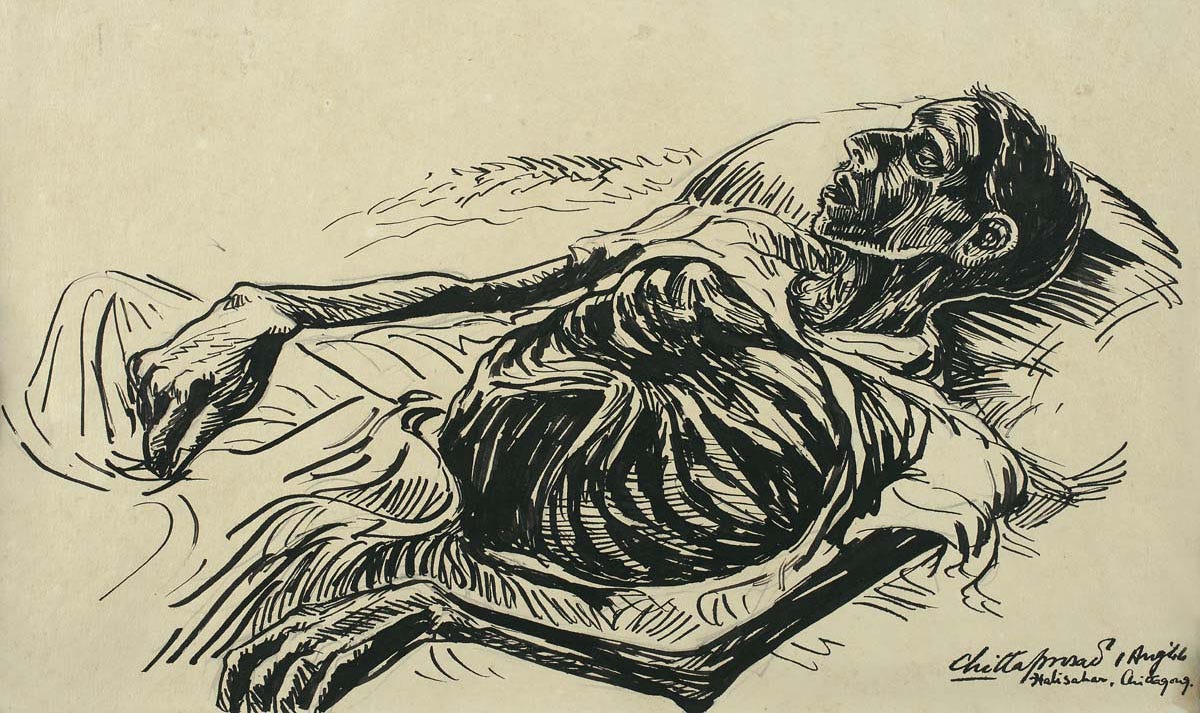

His series of sketches, later compiled in the publication Hungry Bengal, remains one of the most unvarnished accounts of the famine. In these images, the human form is stripped bare — not just by hunger but by the indignities of neglect and abandonment.

A skeletal man cradles his equally emaciated wife; children with distended stomachs, their ribs protruding like scaffolding, stare blankly at a world that has failed them. These artworks were evidence, damning indictments of a colonial system that prioritized empire over humanity.

The British government, recognizing the incendiary power of Hungry Bengal, moved swiftly to ban and destroy copies, but the images had already begun their slow, inexorable seep into the public conscience.

What makes Chittaprosad’s work extraordinary is its refusal to aestheticize suffering. His lines are sparse, his compositions uncluttered, and yet they carry a weight that few more elaborate works could achieve. In his hands, art becomes an act of defiance, a way of reclaiming the humanity of those rendered invisible by history.

There is no romanticization here, no attempt to soften the harshness of reality. Instead, his work forces the viewer to confront, to bear witness, and ultimately to reckon with the moral and structural failures that allow such suffering to persist.

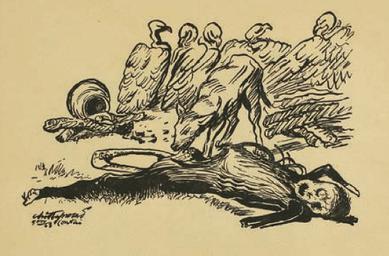

Consider, for instance, his woodcuts — a medium chosen for its starkness and its accessibility. Unlike oil paintings, which were the purview of the elite, woodcuts could be reproduced and disseminated widely, making them a democratic art form.

The stark black-and-white contrast heightens the emotional impact, stripping the scene down to its most essential elements: death and indifference. It is a visual metaphor for a society that feeds on the suffering of its weakest members, a silent yet deafening accusation.

But Chittaprosad’s critique was not limited to colonial oppression. After India’s independence in 1947, his work continued to reflect the inequalities and hypocrisies of the newly formed nation. Independence may have ended foreign rule, but it did little to alleviate the systemic issues that had plagued the country. Poverty, caste discrimination, and political corruption remained entrenched, and Chittaprosad’s art evolved to address these enduring injustices.

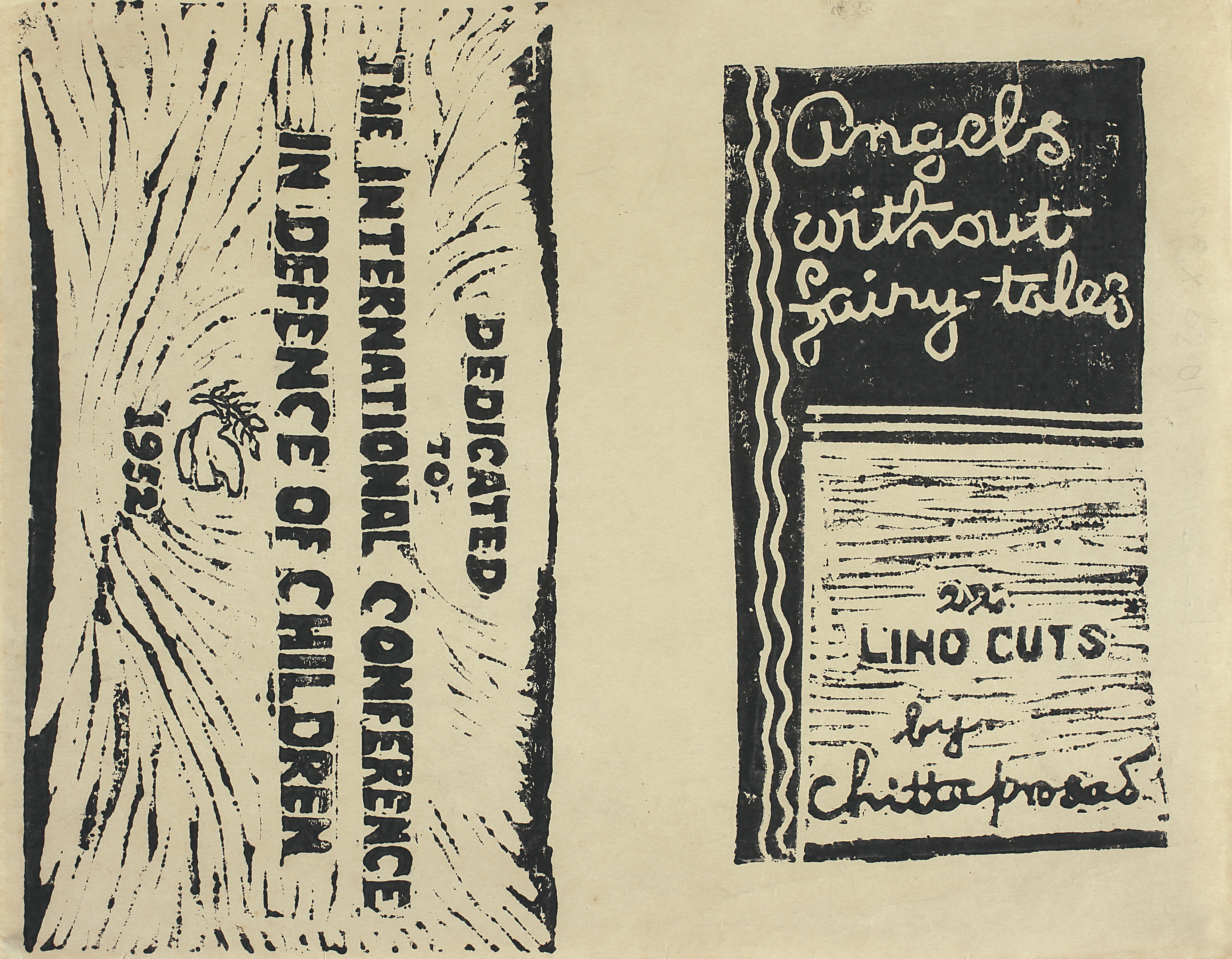

His later works, while less explicitly political, still carried the same moral urgency, focusing on themes of childhood, innocence lost, and the fragile hope that persists even in the direst circumstances.

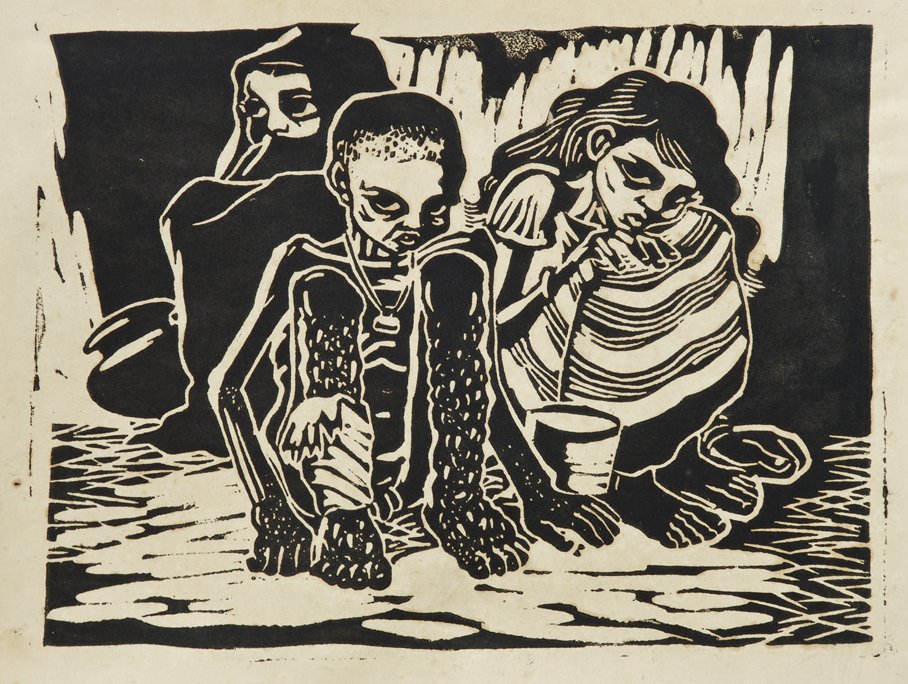

In his series titled Angels without Fairy Tales, Chittaprosad turned his attention to children, portraying them not as symbols of purity or renewal but as casualties of systemic neglect. A young girl, her face marked by premature lines of hardship, clutches a broken toy; a boy stares out from the page, his eyes hollow yet defiant.

These images are not sentimental; they are indictments. By focusing on children, Chittaprosad underscores the intergenerational impact of societal failures. The viewer is left to grapple with an uncomfortable question: what kind of future can emerge from such a broken present?

Chittaprosad’s commitment to social realism set him apart from many of his contemporaries, who often veered toward abstraction or sought refuge in mythological themes. For him, art was inseparable from life; it was a tool for awakening, for challenging complacency.

His affiliation with the Communist Party of India further sharpened his focus on class struggle and the plight of the working poor. Yet, even as he aligned himself with political movements, he maintained an independent voice, refusing to become a mouthpiece for any single ideology. This independence, coupled with his unwavering focus on the marginalized, earned him both admiration and ostracism.

Despite the power of his work, Chittaprosad lived a life marked by material hardship. Unlike many artists who find patronage and acclaim, he remained on the periphery of the art world, his refusal to compromise limiting his opportunities for recognition.

In his later years, he withdrew from public life, devoting himself to quieter pursuits and leaving behind a body of work that continues to resonate. His art, much like his life, defies easy categorization. It is at once deeply personal and profoundly political, rooted in its time yet timeless in its relevance.

Looking back on Chittaprosad’s legacy, his work feels uncannily prescient. The inequalities he documented — the chasm between the haves and the have-nots, the dehumanizing effects of poverty, the systemic failures that perpetuate suffering — remain stark realities in our world.

In a time when images are ubiquitous and often devoid of context, his work reminds us of the power of art to bear witness, to provoke, and to inspire change. His sketches and woodcuts are not just artifacts of a bygone era; they are calls to action, urging us to confront the injustices of our own time with the same unflinching honesty.

In reflecting on Chittaprosad Bhattacharya, one is reminded of the philosopher Theodor Adorno’s assertion that art must resist the commodification of life, that it must stand as a counterforce to the dehumanizing tendencies of modernity.

Chittaprosad’s work embodies this resistance. It refuses to be sanitized, commercialized, or stripped of its urgency. Instead, it demands engagement, challenging us to see not only the suffering it depicts but also the systems and structures that produce such suffering. In doing so, it offers a critique and a vision of what art — and humanity — can aspire to be.

As the world grapples with its own crises — conflict, widening inequality, and the erosion of democratic norms — Chittaprosad’s art feels more relevant than ever. His work reminds us that the pursuit of justice is both an artistic and a moral imperative, that the act of bearing witness is itself a form of resistance.

Leave a comment