Few unfinished projects haunt the imagination like Satyajit Ray’s The Alien. This unmade science fiction film exists as a spectral bridge between the poetic humanism of Indian cinema and the blockbuster sensibilities of Hollywood. It was concieved in the mid-1960s, when Satyajit Ray — Bengali auteur, polymath, and poet of the everyday — turned his gaze toward the stars. His planned film, The Alien, would become a spectral masterpiece, a work that never was, yet one that haunts the canon of science fiction like a shadow cast by moonlight. To trace its contours is to wander through a labyrinth of artistic ambition, cultural dissonance, and the fragile alchemy of what might have been.

Ray, by 1965, had already carved his name into the pantheon of world cinema. His Apu Trilogy — a triptych of films as tender as they are unflinching — had redefined the language of humanism on screen. But Ray was not a man confined to realism. A voracious reader of Wells and Verne, a composer of detective fiction and children’s tales, he harbored a quiet fascination with the speculative. Science fiction, he believed, could be a vessel for the same emotional truths that animated his portraits of rural Bengal — if only one dared to strip away the genre’s pulp veneer.

The seed for The Alien sprouted from a short story Ray penned in 1962, Bankubabur Bandhu(Banku Babu’s Friend). In it, a wide-eyed village boy encounters an extraterrestrial being — a creature of light and empathy, its ship submerged in a lotus-strewn pond. The story was less about intergalactic conflict than about the quiet awe of connection, a theme Ray sought to expand into a feature film.

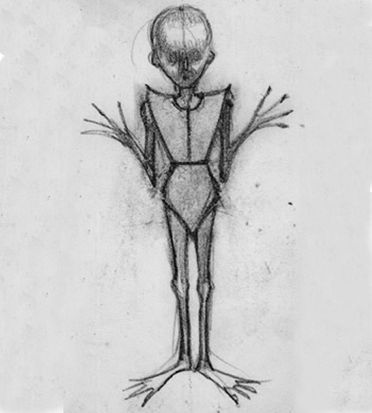

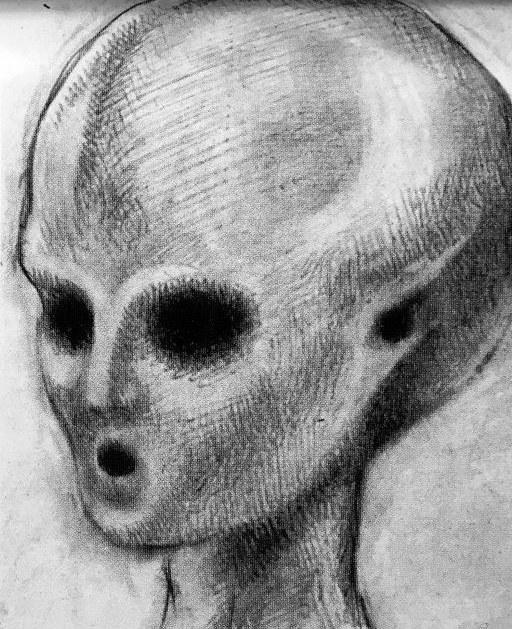

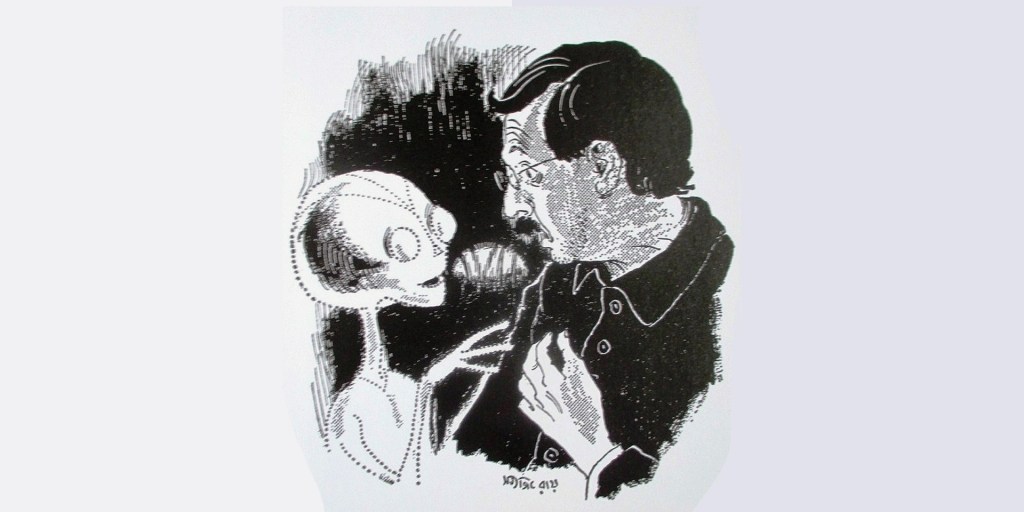

By 1966, he had drafted a treatment, a script humming with his signature restraint. Here, there were no warring empires or dystopian wastelands, only the story of Haba, a Bengali child, and his bond with a stranded alien whose communication transcended language. The being, sketched in Ray’s storyboards as an androgynous figure with translucent skin and eyes like liquid amber, became a mirror for human innocence — a counterpoint to the avarice of outsiders who sought to commodify its mystery.

Fate, or perhaps the caprice of creativity, intervened when Ray crossed paths with Arthur C. Clarke in London. Clarke, then immersed in the cosmic mysticism of 2001: A Space Odyssey, was captivated. He arranged a meeting between Ray and Stanley Kubrick, whose own monolithic vision of space was taking shape.

The encounter, as recounted in Clarke’s letters, was cordial but charged with unspoken tension. Kubrick admired Ray’s “poetic sensibility” but found his vision — a narrative steeped in pastoral wonder — too serene against the stark existentialism of 2001. Yet Clarke’s enthusiasm proved catalytic.

Columbia Pictures, eager to court Ray’s prestige, optioned the script. Marlon Brando, adrift in his post-Godfather mystique, flirted with the role of a cynical American entrepreneur; Peter Sellers, ever the chameleon, considered playing a bumbling priest. For a fleeting moment, The Alien seemed poised to bridge continents, a fusion of East and West, art and spectacle.

But the gods of cinema are fickle. Columbia, seduced by Ray’s reputation yet wary of his unorthodox approach, began to hedge. Executives demanded revisions: shift the setting to America, amplify the action, make the alien “less abstract.” Ray, protective of his parable’s cultural specificity, refused. Negotiations crumbled. By 1969, the project was abandoned, its promise dissolving into the ether. Ray returned to Calcutta, his notes and sketches filed away, a requiem for a film unmade.

Yet stories, like stardust, have a way of traveling.

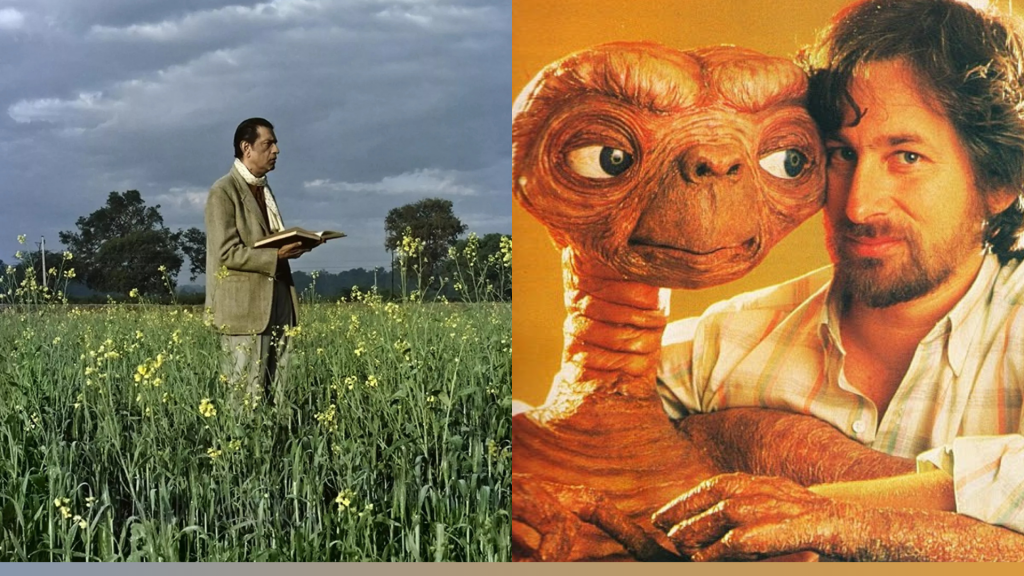

In 1977, a decade after The Alien’s collapse, a young Steven Spielberg unveiled Close Encounters of the Third Kind. The film’s climax—a symphony of light and sound as humans commune with benign extraterrestrials — bore an uncanny resonance with Ray’s vision. Then, in 1982, came E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial. Here was a tale of a child and a lost alien, their bond forged in suburban secrecy, their connection wordless yet profound. Spielberg denied direct inspiration, insisting he’d never seen Ray’s script. But the parallels — the innocent protagonist, the emphasis on empathy over conflict, the adult world’s predatory gaze — struck many as more than coincidence.

The debate over influence is a hall of mirrors. Screenwriter Melissa Mathison claimed no knowledge of Ray’s work; Spielberg’s team emphasized E.T.’s organic evolution from the director’s childhood fascination with imaginary friends. Yet film historians note that Ray’s treatment circulated among Hollywood insiders in the 1970s, a whispered legend of a lost masterpiece. Whether through osmosis or archetypal convergence, the kinship between the two films transcends mere plot points. Both are meditations on loneliness and connection, on the primal urge to reach across the void — whether cosmic or emotional.

But to reduce The Alien to a footnote in E.T.’s genesis is to miss the deeper tragedy. Ray’s unmade film was not merely a casualty of creative differences; it was a casualty of cultural myopia. Hollywood, in the 1960s, could not fathom a science fiction epic rooted in Bengali soil, where the alien’s ship hid not in a Spielbergian suburb but among rice paddies and monsoon rains. Ray’s vision demanded that Western audiences see themselves refracted through an Eastern lens — a prospect as radical then as it remains fraught today. His alien, conceived as a silent observer of human folly, was a critique of colonialist greed, a theme that might have resonated in a post-Vietnam era. Instead, it became a relic, a testament to the industry’s inability to imagine universality beyond its own borders.

Decades later, fragments of The Alien persist like shards of a shattered mirror. In 1987, Ray adapted his script into a Bengali novella, The Alien: Stories of Science Fiction. His son, Sandip Ray, later unearthed storyboards and musical notes, revealing a vision both intimate and expansive. Scholars like Andrew Robinson, Ray’s biographer, argue that the film’s DNA surfaces in works as disparate as Tarkovsky’s Stalker and Bong Joon-ho’s The Host — films where the speculative is a scalpel, not a sledgehammer.

What endures is not the question of influence but the parable of artistic transcendence. The Alien’s demise mirrors the fate of countless works that dare to exist outside dominant narratives — stories silenced by circumstance, yet whose echoes ripple through time. Spielberg’s E.T., for all its Hollywood sheen, channels a spirit Ray first kindled: the belief that wonder is not the province of spectacle, but of the human heart’s quiet revolutions.

Ultimately, films may remain unshot, scripts may yellow with age, but the stories we almost tell — the ones that flicker at the edge of consciousness — never truly vanish. They linger in the collective imagination, waiting to be born anew, in another time, in another form. The Alien, like its titular creature, belongs now to the cosmos, a celestial whisper in the endless dialogue between art and possibility.

Leave a comment