In the golden haze of a colonial era afternoon in Bengal, the fields stretch endlessly, a sea of nodding poppies under the relentless sun. Each bulbous seedpod, slit by the blade of a khasdar—the opium collector—weeps its milky sap, a viscous elixir that would travel across oceans, empires, and centuries. This was not agriculture but alchemy: a colonial metamorphosis of pain into profit. By the mid-19th century, Bengal had become the throbbing heart of a global narcotic empire, its veins pumping opium to the farthest reaches of British dominion. The story of how this fertile delta, crisscrossed by the Ganges and Brahmaputra, transformed into the opium capital of the British Empire is one of coercion, calculation, and the quiet violence of bureaucracy.

The East India Company’s entanglement with opium began not in Bengal but in the ledgers of trade deficits. By the 18th century, Britain’s thirst for Chinese tea—once a luxury sipped by aristocrats—had become a national addiction, draining silver reserves to pay Qing merchants who demanded hard currency. The solution, as the Company’s sharp-eyed accountants realized, lay in a triangular trade: Indian opium for Chinese tea, tea for British tables, and profits for shareholders.

Bengal, with its fertile soil and compliant peasantry, was chosen as the laboratory for this grand experiment. In 1773, the Company established a monopoly over opium production in the region, a move that would bind the destinies of millions to the whims of distant markets.

What followed was not mere commerce but a feat of social engineering. The Company, and later the British Crown, constructed an intricate machinery of control. Peasants in Bihar and Uttar Pradesh—often landless, always indebted—were lured into contracts with advance payments, a seemingly benevolent gesture that masked a trap.

These advances, interest-free but non-negotiable, locked cultivators into cycles of production. The opium agent, a figure both feared and obsequiously obeyed, became the arbiter of rural life. He dictated the acreage to be sown, inspected each poppy field with a taxidermist’s precision, and imposed fines for underweight harvests. The peasant, as Rolf Bauer’s meticulous research reveals, became a “bonded actor in a colonial drama,” compelled to grow a crop that cost more to produce than it earned. Opium, in this calculus, was not a choice but a corvée.

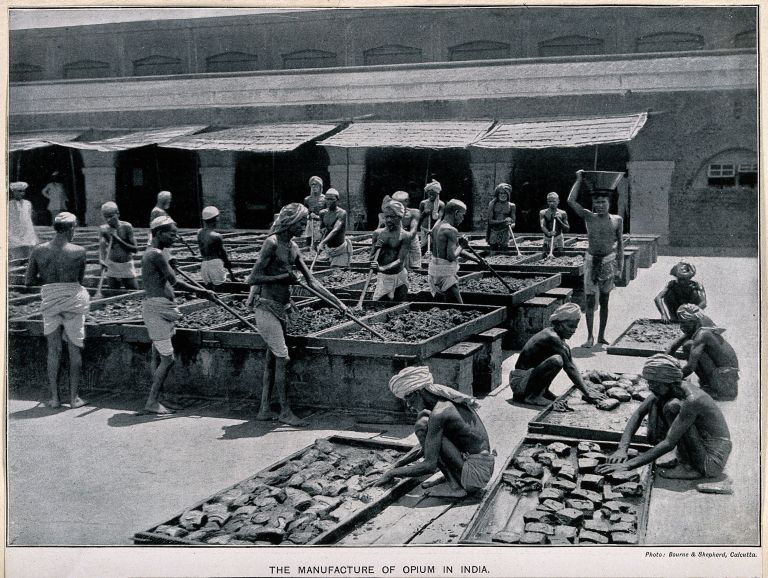

The factories of Patna and Ghazipur stand as monuments to this engineered economy. Here, the raw sap was kneaded into cakes, stamped with the colonial seal, and packed into chests bound for Calcutta’s auctions. The process was militarized in its efficiency: thousands of workers, their hands stained black by opium residue, labored under the watch of European supervisors. The scent—musky, cloying, inescapable—permeated the air for miles. By the 1830s, these factories processed over 6,000 tons of opium annually, feeding a habit that would ignite wars and redraw maps.

The true genius—or malignancy—of the system lay in its indirect rule. The British relied on a web of local collaborators: zamindars (landlords) who enforced cultivation targets, village headmen who mediated disputes, and a clerical army of 2,500 opium agents who transformed agrarian rhythms into quarterly reports. This decentralized despotism allowed the colonial state to extract wealth without the messy burden of direct governance.

As Samuel Betteridge’s analysis of the opium monopoly notes, the British prioritized “informationally light” revenue streams, avoiding the administrative heavy lifting required for income or property taxes. Opium, in other words, was not just a commodity but a fiscal sleight-of-hand, enabling the Empire to profit without the inconvenient demands of accountability.

The human cost was measured in silent tragedies. A farmer in Saran district, having dedicated half his land to poppy, found himself unable to grow enough food to feed his family. A widow in Ghazipur, her husband dead from an overdose of the very drug he processed, discovered that her compensation was a pittance deducted from his final wages.

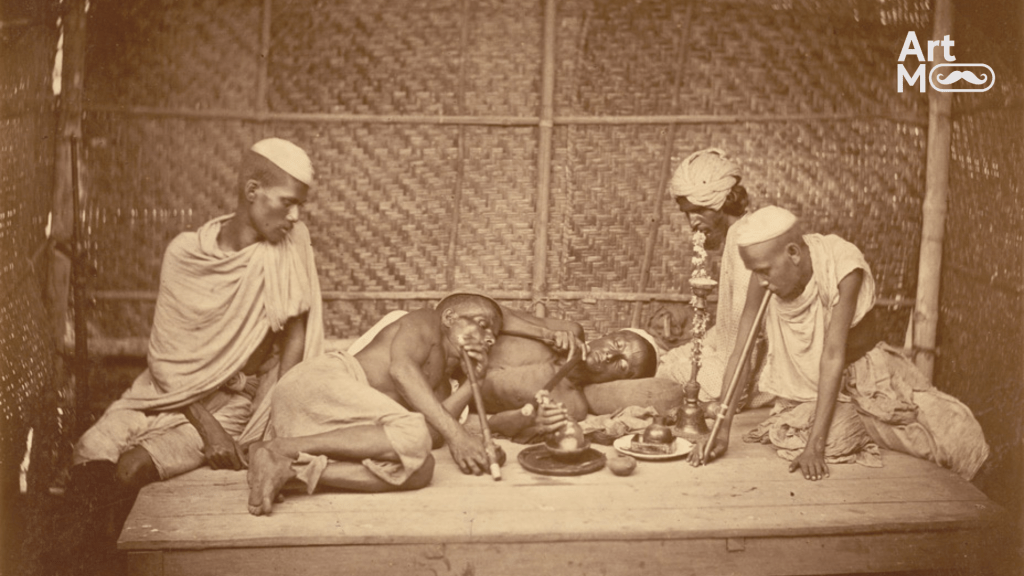

The Royal Commission on Opium of 1895, a sprawling Victorian inquiry, documented these realities with clinical detachment. Witnesses testified to addiction, coerced cultivation, and the collapse of food security. Yet the Commission’s final report, steeped in the racial paternalism of the age, concluded that opium was a “natural” vice for Asians, a cultural proclivity that justified its commodification. The poppy, it seemed, had colonized not just land but imagination.

China, of course, was the unwitting accomplice in this tragedy. The chests of Bengal opium, unloaded at Canton’s wharves, fueled an epidemic that hollowed out communities and destabilized the Qing dynasty. When the Chinese emperor dared to resist—burning British opium stocks in 1839—the response was a naval bombardment masquerading as free trade.

The Opium Wars, those twin spasms of imperial violence, were less about “opening markets” than preserving the economic architecture that made Bengal’s fields indispensable. Hong Kong, seized as a trophy in 1842, became both entrepôt and symbol: a node in the narcotic network that linked Calcutta to London.

Yet to reduce this history to a tale of victimhood is to miss its paradoxical resilience. The same peasants who were coerced into poppy cultivation occasionally turned the system against itself. Some diluted opium resin with sandalwood paste to meet weight quotas; others “lost” harvests to mysterious blights.

These acts of sabotage, though rarely recorded in official ledgers, hint at a subterranean resistance—a quiet insistence on agency amid the machinery of extraction. Even the soil itself seemed to rebel: by the late 19th century, over-cultivation had depleted the land, forcing the opium agency to shift operations westward. The poppy, it turned out, was a demanding lover, exhausting its suitors even as it enriched them.

By the early 20th century, the edifice began to crumble. International condemnation, spurred by missionary groups and temperance leagues, painted the opium trade as a moral blight. China, wracked by revolution, finally closed its ports to Indian opium in 1915. Yet the British, ever pragmatic, simply redirected the supply to Southeast Asia and the Middle East. The monopoly endured, a zombie enterprise, until independence in 1947 severed the colonial sinews that sustained it.

Today, the ghosts of this history linger. The Ghazipur factory still produces opium for pharmaceuticals, a legal heir to its illicit past. In Bihar’s villages, elders recount stories of great-grandfathers bound to the poppy, their fates dictated by a distant queen-emperor. And in the global discourse on drug policy, the Bengal model haunts like a specter—a cautionary tale of how commerce, when divorced from ethics, can enslave even its architects. The British Empire has long since dissolved, but the poppy’s shadow still stretches across time, a reminder that the past is never truly processed—only metabolized, slowly, in the bloodstream of history.

Leave a comment