Imagine, if you will, a society where the air itself seems to curdle with unspoken rules—where a woman’s glance, a Dalit’s shadow, or a widow’s sigh could unravel the fragile fiction of “order.” Now place a writer in this world, one who neither brandishes a manifesto nor strikes a martyr’s pose, but instead crafts stories so disarmingly human that they become Trojan horses for rebellion.

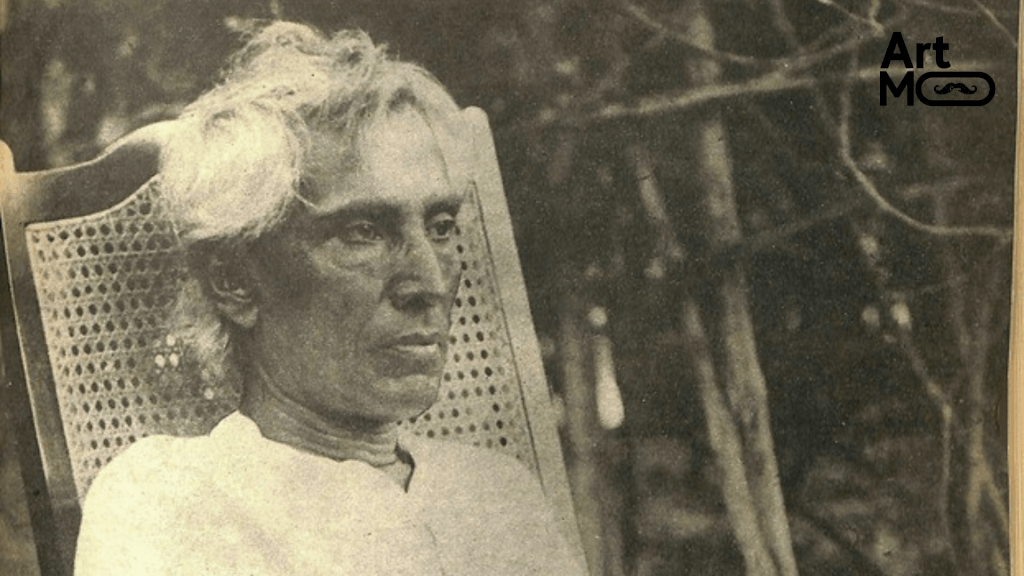

Sarat Chandra Chattopadhyay, often mistaken for a sentimental chronicler of Bengali domesticity, was precisely this kind of literary saboteur. His works—steeped in the rhythms of village life, yet crackling with subversive wit—did not merely document the caste and gender tyrannies of early 20th-century Bengal; they dissected them with the clinical precision of a biologist studying a malignant tumor. To read him is to witness a man juggling lit dynamite while whistling a tune about love and loss, all the while knowing the explosion would leave society’s pretensions in tatters.

While Tagore soared into metaphysical realms and Bankim Chandra weaponized nationalism, Sarat Chandra rooted himself in the mud and marrow of everyday suffering. His characters—a widow sneaking a bite of fish, a Brahmin boy sharing a meal with a Dalit friend, a prostitute lecturing a judge on ethics—are not symbols but insurgents in plainclothes. They violate taboos with the casualness of someone rearranging furniture, exposing the absurdity of hierarchies upheld as divine law. If Jane Austen taught us to laugh at the British aristocracy’s mating rituals, Sarat Chandra turned that same sardonic gaze on Bengal’s sanctimonious bhadralok, revealing their moral contortions to be as farcical as a poorly staged jatra play.

Consider the sheer audacity of his timing. Chattopadhyay began publishing in the 1910s, an era when Bengal’s intelligentsia was busy debating whether to blame the British or Kali Yuga for societal decay. Meanwhile, in drawing rooms from Calcutta to Comilla, women were still being barred from eating before men, and Dalits were beaten for accidentally casting their shadows on a Brahmin’s meal.

Caste, in his world, is a shapeshifting monster. In Brahman ki Beti (1920), a Brahmin girl’s elopement with a Kayastha man exposes the farce of “purity.” Her father, who once quoted the Manusmriti like scripture, abruptly rewrites tradition to salvage his social standing. The satire here is so sharp it could slice through a sacred thread: Sarat Chandra mirrors Flaubert’s mockery of bourgeois morality in Madame Bovary, but swaps French ennui for Bengali adda, where hypocrisy is debated over cups of cha and plates of telebhaja.

Gender, however, is where his scalpel cuts deepest. His women refuse the binary of “goddess or gutter.” Consider Borodidi from Charitraheen (1917), a widow who dares to seek companionship after years of enforced austerity. Society brands her a deviant, but Sarat Chandra frames her desire as an act of quiet rebellion—a Bengali Edna Pontellier, if Chopin’s heroine had traded Grand Isle’s sea breeze for the claustrophobia of a Calcutta bustee. Unlike Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina, Borodidi isn’t punished with death; she’s condemned to something worse: living in a world that shrinks her humanity to a cautionary tale.

Even Devdas, often reduced to a maudlin love saga, hides a stealthy indictment of patriarchal fragility. Devdas’s self-destruction isn’t romantic tragedy but a case study in male entitlement. Paro, his childhood love, marries another but survives with her dignity intact; Chandramukhi, the courtesan, builds agency within her circumscribed world. Devdas, meanwhile, drowns in a pool of self-pity and brandy, his demise a metaphor for a system that equates masculinity with self-immolation.

Take Mahesh (1917), a story often misrepresented but devastating in its actual critique. Here, a Dalit groom named Mahesh is falsely accused of stealing his employer’s gun. Without trial or evidence, a mob of upper-caste men lynches him, their violence masquerading as justice. Sarat Chandra’s narrator—a privileged bystander—laments, “We killed him not because he was guilty, but because we could” (condensed interpretation). The story isn’t about individual villainy but the collective hysteria of caste, a theme that resonates with the lynching narratives of Faulkner’s American South. Yet Sarat Chandra’s critique is distinct: his prose simmers with a quiet rage, as if the ink itself were stained with the blood of the oppressed.

Sarat Chandra’s global analogues are legion—the social satire of Dickens, the feminist ire of Charlotte Perkins Gilman, the absurdist edge of Gogol—but his voice remains unmistakably rooted in Bengal’s soil. His stories are not calls to arms but whispers in the dark, urging readers to question why a society that worships goddesses reduces women to ghosts, or why a land obsessed with dharma tolerates the indecency of caste.

His humor, often overshadowed by his pathos, is the spoonful of sugar that makes the critique go down: a widow outwitting pandits with Vedic loopholes, a landlord’s son getting schooled by a sex worker, a Brahmin’s sanctimony punctured by a well-timed sneeze.

Today, as India’s caste and gender wars play out on Twitter feeds and courtrooms, Sarat Chandra’s work feels less like period fiction and more like a mirror held up to our present. The chains have evolved—from ostracism to online harassment, from temple bans to honor killings—but their weight remains familiar.

To read him now is to realize that progress is not a switch flipped by reformers but a slow, grating rotation, powered by ordinary people who, like his characters, refuse to accept that the world must forever bend to the logic of its cruelest norms. His stories remind us that every revolution begins not with a slogan, but with a question: Why should this be so? And sometimes, that question is enough to make the chains fall away.

Leave a comment