Imagine, if you will, a land where grandmothers are archivists, their tongues flicking like lizard tails to dust off epics stored in the attics of their throats. Where illiterate bards recite genealogies longer than monsoon rivers, and a single folk song contains more encrypted history than a blockchain ledger.

India’s oral storytelling traditions do not “preserve” cultural knowledge in the manner of a librarian pressing flowers between pages; they ferment it, like a row of terracotta pots left bubbling in the sun, transforming raw facts into intoxicating rasam of memory.

Here, the past is not embalmed—it is pickled, with all the pungent vitality that implies. To reduce these traditions to mere vessels of transmission is to mistake the dancer for the floorboards. They are, instead, a kind of anti-archive: anarchic, adaptive, and deliciously allergic to the tyranny of the fixed text.

Consider the Bauls of Bengal, those madcap mystics who’ve turned oral transmission into a high-wire act between the sacred and the scandalous. Their songs—part parable, part absurdist joke—insist that God resides not in temples but in “the ant’s heartbeat,” and that scriptures are useless unless chewed, swallowed, and excreted as wisdom. Try preserving that in a museum vitrine.

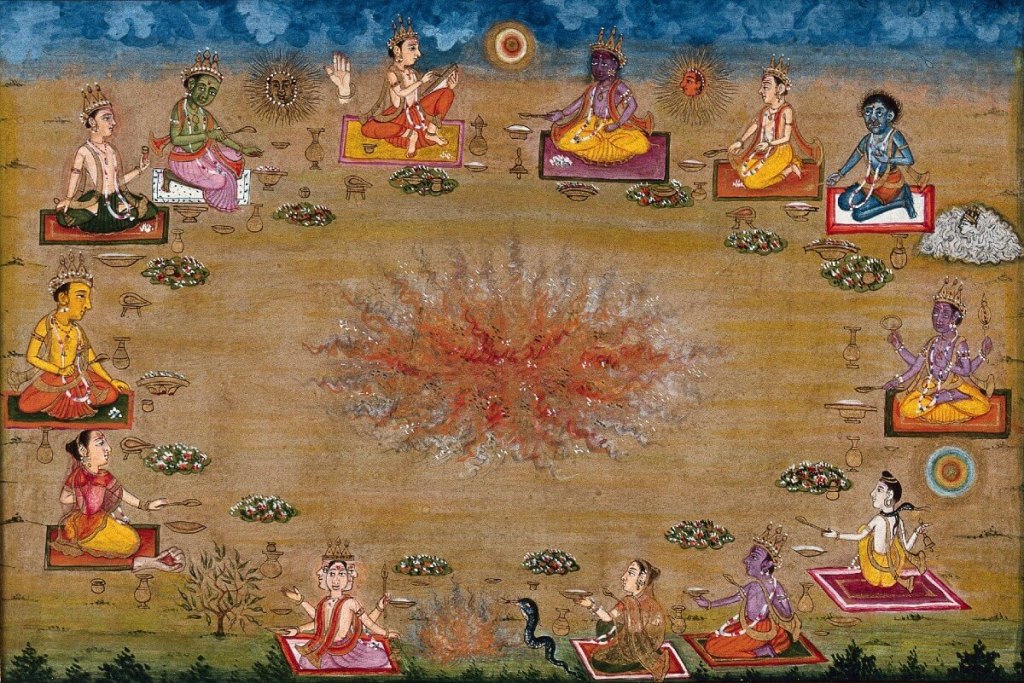

Consider the Vedic corpus, the primordial wellspring of this tradition. The Rig veda, a staggering 10,600 verses, was transmitted orally for over 3,000 years before being committed to script—a feat that would make even the most disciplined modern mnemonist shudder.

This was no haphazard recitation but a meticulously engineered system of patha, or recitational techniques, involving eleven forms of phonetic permutations to prevent even a syllable’s deviation. The ancients, it seems, understood that memory is not a passive vessel but an active ritual—a dance of cognition where rhythm, pitch, and repetition coalesce into an unbroken chain of knowledge. One might jest that if today’s students grumble over memorizing a sonnet, their Vedic predecessors would have chuckled while juggling entire Upanishads in their minds, all while debating the ontological nuances of Brahman.

But oral storytelling in India was never confined to the sacerdotal elite. It spilled into the bazaars, temples, and village squares, morphing into a democratic pedagogy. The Panchatantra, that wily menagerie of animal fables, was not merely entertainment but a Machiavellian manual for statecraft, disguised as a jackal’s cunning or a tortoise’s prudence. Its tales migrated westward, shaping Aesop’s fables and the Arabian Nights, yet few recognize that the original “story within a story” structure—a narrative matryoshka—was born in the Indian imagination.

Similarly, the Jataka tales, with their moral parables of the Buddha’s past lives bound communities through shared ethical frameworks. The genius lies in their fluidity: a single story could be a child’s bedtime tale, a merchant’s lesson in integrity, or a king’s treatise on governance, depending on the teller’s inflection and the listener’s station.

The performative dimensions of these traditions reveal another layer of sophistication. Take Kathakalakshepam, where a storyteller—part philosopher, part bard—weaves Sanskrit shlokas with Tamil folk melodies, punctuating tales of Shiva’s cosmic dance with digressions on metaphysics. Or the Yakshagana of Karnataka, where epics are not recited but embodied through dance, music, and elaborate costumes, transforming the Ramayana into a multisensory spectacle that even the illiterate farmer could decode.

The rasa theory of aesthetics, articulated in Bharata Muni’s Natyashastra, formalized this interplay: each story was designed to evoke specific emotions (bhava) that led to universalized emotional essences (rasa), whether the erotic shringara or the heroic vira. To witness a Kathakali performance—where a dancer’s raised eyebrow could signify Ravana’s hubris or Sita’s anguish—is to grasp how oral traditions fused art and intellect into a single gestalt.

Yet the true subversion lies in the oral tradition’s resistance to canonization. Unlike the Abrahamic faiths’ obsession with unalterable scriptures, India’s stories thrived on plurality. The Ramayana exists in 300 regional variants—a Tamil Kampan’s rendition exalts Rama as a divine king, while a tribal Bhil version paints him as a flawed mortal navigating ethical quagmires 710. This elasticity allowed narratives to adapt to local cultures without losing their core dharmic essence.

Even the Mahabharata, that grand treatise on existential chaos, acknowledges its own mutability in the Adi Parva: “What is found here may exist elsewhere; what is not here exists nowhere.” The irony is delicious: a text celebrating its incompleteness becomes the most complete mirror of human frailty.

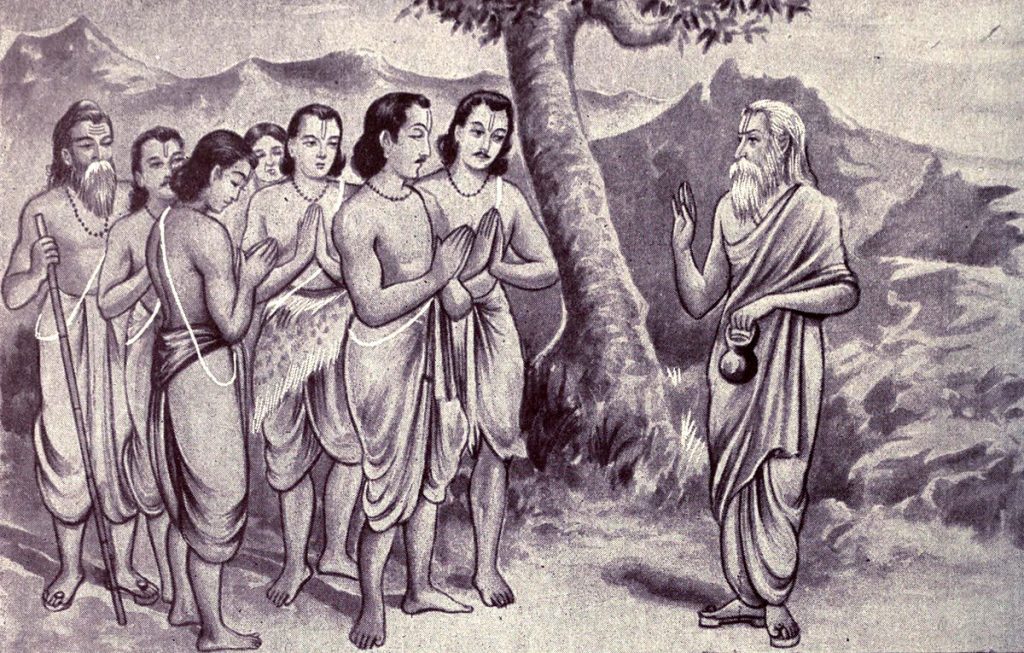

The mechanisms of preservation were equally ingenious. The guru-shishya parampara was a teacher-student dyad and also sort of a living library. Students memorized texts through call-and-response rituals, internalizing knowledge as a somatic practice. Commentaries (tika) and recensions ensured that texts like Panini’s Ashtadhyayi—a grammatical masterpiece denser than black holes—could be decoded across centuries.

The patha tradition involved reciting texts in reverse, diagonally, or in fragmented clusters, a cognitive jigsaw that safeguarded against erosion. One imagines these ancient scholars as intellectual tightrope walkers, balancing verbatim accuracy with interpretative innovation.

Modernity, of course, has not been kind to this legacy. The colonial fetish for written archives dismissed oral traditions as “primitive,” while today’s digital deluge threatens to drown the intimate cadence of the storyteller’s voice. Yet, resilience persists. Initiatives like Rajasthan’s Pabuji ki Phad—where itinerant bards unfurl scrolls to sing of a deified folk hero—or Tamil Nadu’s Villu Paatu, where tales are sung with a bow-shaped lute, adapt ancient forms to contemporary contexts.

Even the secular has become sacred: Mumbai’s Dastangoi performers revive the Urdu art of epic storytelling, proving that Scheherazade’s spirit lives on in the unlikeliest of metropolises.

But let us not romanticize. The decline of oral traditions is a civilizational crisis. When a Baul minstrel’s song fades in Bengal, or a Burra Katha drummer in Andhra forgets his beats, we lose not just art but a way of knowing. Orality’s strength—its fluidity—is also its vulnerability.

Unlike a clay tablet or a PDF, a story untold is a story extinguished. Yet, herein lies the paradox: the very impermanence that threatens these traditions also embodies their philosophical essence. The Buddhist doctrine of anicca (impermanence) or the Hindu concept of maya (illusion) remind us that all forms are transient. Perhaps oral traditions, in their evanescence, teach us to hold knowledge lightly—to cherish it not as a monument but as a river, ever-flowing, ever-changing.

In closing, one is reminded of the Kathasaritsagara, the “Ocean of the Streams of Stories,” where tales cascade into tales ad infinitum. To dive into this ocean is to confront a profound truth: Bharat’s oral traditions are not mere vehicles of cultural knowledge but the very water in which that knowledge swims. They defy the tyranny of the written word, offering instead a participatory epistemology where every listener becomes a co-creator, every telling a renewal.

In an age where information is cheap but wisdom scarce, these traditions whisper a subversive question: What if true preservation lies not in fossilizing the past but in letting it breathe, mutate, and dance on the tongues of the living? The answer, perhaps, is etched in the fading echo of a grandmother’s tale, or the rhythmic clap of a village storyteller—a reminder that culture, at its core, is not stored but sung.

Leave a comment